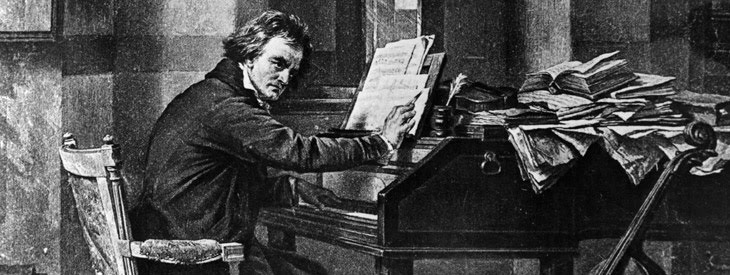

There is a wonderful painting of Beethoven composing I have cited at the top of this post which I find most fascinating. It perfectly represents exactly what I envision it might have been like to watch Beethoven compose – lost in thought, papers scattered everywhere, seated at the piano trying to find the right notes for the next phrase or chord progression. On the surface, it would appear Beethoven is the embodiment of total disorganization – unkempt, wild hair, piles of papers in no apparent order, yet in his music, and most especially his early works, I hear not disorganization, but a total mastery of form and very careful planning and organization, as he learned from the great Classical masters Haydn and Mozart before him. In his first set of six string quartets, Op. 18, Beethoven demonstrates complete command of the Classical style, paying homage to Haydn and Mozart, while also making the Classical style his own, with his personality shining through in these relatively “behaved” pieces of music compared to his later works. This is also clearly evident in his first two symphonies and piano concertos, not to mention his early cello sonatas, violin sonatas, piano sonatas, and other beautiful chamber works he composed with an assuredness of being the equal of Haydn and Mozart. It is quite impressive how Beethoven, under what must have been the overpowering shadow of Haydn and Mozart forged ahead to establish himself as the next great Viennese composer. It had to have taken an incredible amount of courage and self-confidence to pull this off, and he succeeded brilliantly. It was a character trait that little did Beethoven know then, would be indispensable for him to survive the crushing trials that were ahead of him.

It is amazing how Beethoven could have found such beauty, coherence, and clarity in his music as his world and his own personal life was crumbling around him – with the French occupation of Vienna and Napoleon’s Army shelling the city, the gradual loss of his hearing, his eventual early retirement as a pianist after his last public performance on the concert stage at the age of 38 at his December 22, 1808 concert, and the breakdown of his relationship with his nephew Karl. It is incredible how he had the ability to keep his sanity well enough to enable him to continue to compose some of his most beloved and enduring masterpieces such as the 9th Symphony, his last string quartets, and his Missa Solemnis. Other people of a less courageous and a weaker constitution would have simply folded, gone insane, created nothing further, or committed suicide – an option Beethoven seriously considered more than once in his life, and especially at Heiligenstadt, where he wrote his famous testament reflecting his despair over his increasing deafness.

But Beethoven’s will was extraordinary. With more defiance and determination than ever, he emerged from Heiligenstadt committed to live for his art, and to go in a new direction creatively. He may well have been the most strong-willed and courageous artist in the history of music. It is one of the reasons we identify with him – because his struggles are our struggles. He rises above his adverse circumstances and emerges triumphant. He is the underdog, the champion of the everyman. He is an ordinary person who does extraordinary things. In many ways, he is a hero. It is no coincidence his middle creative period after Heiligenstadt is often referred to as the “heroic” period which saw the composition of his heroic, “Eroica” Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, the 4th and 5th Piano Concertos, the Razumovsky Quartets, the “Kreutzer” Sonata for Violin and Piano, and the 4th through 8th Symphonies to name only some of his middle period works.

It can be said that Beethoven took on every challenge life threw at him musically, and found a way to answer that challenge masterfully. However, he was a continual failure in his personal life, never able to find lasting love in a lifelong mate, and was so overbearing to his adopted nephew Karl that he eventually attempted suicide. Beethoven is the classic example of an extremely gifted, abused child. Like most people who are abused, he ended up abusing others – most especially his nephew and lived to regret it. In many ways, Beethoven’s story is a tragic story, and perhaps more than any other illustrates the incredibly high price of genius – a life lived in isolation, married to one’s work, socially inept, and producing creative riches which reflect the beauty of life in all its fullness and joy, sorrow, and longings, yet one which ironically makes the creator themselves unable to personally participate in that life to the fullest. In a sense the creative genius is like a soldier who gives their life not so they may live a better life, but so others might. The creative genius gives their life to their art. It is those after them who enjoy the fruits of their incredible sacrifice and labor. We see how composers like Brahms, Schubert, and Tchaikovsky had to accept a life of general solitude in commitment to their work. Mahler’s marriage failed in part because of his single-minded and impassioned dedication to his work at the expense of his marriage, and because he forbade his wife Alma to compose. He could never find a balance and his personal life suffered because of it. In some ways, it seems there is not enough room for both – for total commitment to one’s art and to living. For the creative genius this is an impossible situation, because they cannot deny either side to them, but feel they must choose.

Mozart tried to find a middle ground between living and being committed to his art. He knew he needed a marital partner, and found one in Constanze Weber. Together they had six children, only two of which survived infancy. While Mozart tried to have a “normal” domestic life, and his surviving letters to his wife reveal himself to be an affectionate, loving, protective, and sometimes jealous and possessive husband, it is hard to imagine exactly how involved as a father and husband he could have possibly been given his almost superhuman compositional production, not to mention the innumerable concerts, rehearsals, meetings with librettists, royalty, collegues and friends, billiard playing, and entertaining he did in his home. It is no wonder his light burned out only too quickly. He tried to do it all – to live fully and be an artist fully, but he could not keep up the pace. He paid the price with his life, as Beethoven did, but in a different way.

I recognized this dilemma of the conflict between living and being an artist for myself when I was studying to be a composer while in college. The film “Amadeus” inspired me to decide to become a composer at age 13. I naively thought if I worked hard enough I could “catch up” and become another Mozart. It is with the deepest humility I can now say almost 30 years later, I never had any chance at that, because the likes of a talent like Mozart’s and Beethoven’s has not been seen since, and may never be seen again. While musically talented, I am nowhere close to either man in ability. I thought it would be great to be a genius like Mozart. How naive I was, as I did not then realize the incredibly high price of genius, and what it meant to be enslaved to one’s work in many ways, even if it is so often a joy. I did very well in college, and wrote some very good music while in school, and especially after I graduated. While I can say I have perhaps had some “ingenious” moments as a composer, I certainly never lived as one the way Beethoven and Mozart did, who dedicated their entire lifetime to music. I have several other interests in addition to music, a desire to live life, to work on my relationships with others as passionately as I pursue my artistic endeavors, and so I can say now, in retrospect how glad I am not to be a genius as they were. I can enjoy the fruits of their labors, admire them, appreciate them, and perhaps say a word or two which might at least somewhat reflect the incredible impact they have on those who sincerely appreciate what riches they have given us through their sacrifice…