In my last post, I discussed some of the main differences between Classicism and Romanticism, and in the post before that, we discovered through the analysis of different composers’ mastery of various genres of music, that in my opinion, Mozart is the greatest composer of all time, and why I ranked other composers as I did. While discussing music this weekend with my best friend from college, we discovered what it is that truly makes Classical era music different from music of other eras, and especially why Mozart’s music stands out among all other music across all eras. Classicism is the ideal of perfect balance, harmony, and symmetry of line, form, and expression through contrast. It is an ideal which is not about emotion, but about the expression of different “shades” or “colors.” In the Classical ideal, it is never about “me,” about “I.” It is not about how the composer “feels” about something, but about manifesting what is. While the Romantic writes about how the sunset makes them feel, the Classicist writes the beauty of the sunset itself. To do this, one’s emotions cannot overshadow or cloud the pristine beauty of what it is one is expressing. Everything must have clarity, and emotions do not clarify, but cloud.

This is why personal emotional expression was not desired in the Classical era. It clouded the realization of the Classical ideal during the Age of the Enlightenment in which reason, logic, clarity, and structure were of supreme importance. It is precisely this ideal Beethoven rebelled against because his ideal was that of a Romantic – of personalized self-expression. This may be one reason for his lack of contentment with his teacher Haydn, whom Beethoven likely found to be too “rigorous” and “old fashioned” in his Classical ideals Beethoven would ultimately reject. I can remember while thinking of Mozart not too long ago, realizing there was “something missing” in his music which I can hear in all other music. This struck me as odd since Mozart’s music is often lauded as some of the most “divine” and beautiful music ever written. You would think there would be nothing missing in it. However there is something missing, and that something is the “I.” There is no “I” in Mozart. As I said in my last post, with Mozart there seems to be a kind of “detached” quality in his music which is not present in any other music, not even Bach. While I feel Bach is very much like Mozart in that you cannot know the man through the music, Bach’s music is about emotional expression, as he was a Baroque composer during an era in which emotion was desired, but not personal expression of emotion. While this makes his music not “about Bach” specifically, it is or at least can be about emotion, which is necessarily centered on the concept of the self, the “I,” because without the “I,” emotion does not exist.

This lack of “I” in Mozart’s music can be heard in the absence of any “personal” interjection as we hear in Haydn and Beethoven. Mozart remains without personal “comment” and simply reveals perfect clarity of line, structure, and balance time and time again in one masterpiece after another. It is precisely this quality which makes people call his music “divine,” as it is without humanity because it is without emotion. It is just pristine, uncluttered beauty, devoid of all which would cloud its beauty, which makes his music the pinnacle of the Classical ideal. This is also why Mozart’s music, while often considered “divine,” can at the same time be disturbing for some people, even on occasion called “insane,” and sometimes “superficial.” It is generally not a lack of depth in Mozart’s music which bothers some people, as much of Mozart’s music is quite profound, but its absence of humanity and its pristine perfection which is so unlike who we are as flawed, imperfect people. However for me, when I want purity of sound and to “remember” the oneness and perfect balance of the universe, I listen to Mozart. The sound of his music is the sound of perfection, the sound of the perfect unity of oneness. This is ultimately why Mozart is the greatest of all composers for all time – not only because of his mastery of all forms, but also because his music is the perfect reflection of the perfect order, beauty, and oneness of the universe. The truth of oneness is egolessness, and it is only in Mozart’s music where the “I,” the ego is absent. Where there is no “I,” there is no perception of time, and only the bliss of now. Without the “I,” there is also no judgment. Mozart’s music is without judgment because the “I,” the ego is not present in it. He only reveals what is in his music, without personal comment or judgment. Unlike the music of any other composer, Mozart’s music perfectly reflects this selfless, egoless perfection, which is why it is rightly called “divine.”

Interestingly enough, this was not the man Mozart himself, who could be proud, arrogant, rude, judgmental, and very critical of others. While Mozart also had positive qualities such as being kind, loving, generous, and loyal to his friends, his character flaws resemble the mirror opposite of his music, and may be the best proof of all how for Mozart, the music was not the man. While the film “Amadeus” was largely fictional, this fact of the disconnect between Mozart the man and Mozart’s music was perhaps the most accurate part of the film. It was this aspect of Mozart which most confounded Salieri, and was perfectly reflected in a line from the film in which Mozart says to the Emperor Joseph II, “Forgive me majesty. I’m a vulgar man. But I assure you my music is not.” The fact he could compose opera from the age of twelve while being able to create music perfectly appropriate for complex emotional situations in storylines prove his music was not about “personal experience” or emotion. If it was, he would not have had the emotional maturity to compose opera, because at twelve years old he had not yet reached puberty and had not experienced the complex hardships, joys and trials of adulthood. Throughout Mozart’s life, even in adulthood, his letters reveal himself to be sometimes immature and emotionally needy and underdeveloped. If this was the man who created profound messages musically and dramatically in opera, then he could not be ranked as one of the top three opera composers of all time if writing opera demanded it reflect his own personal and emotional experience.

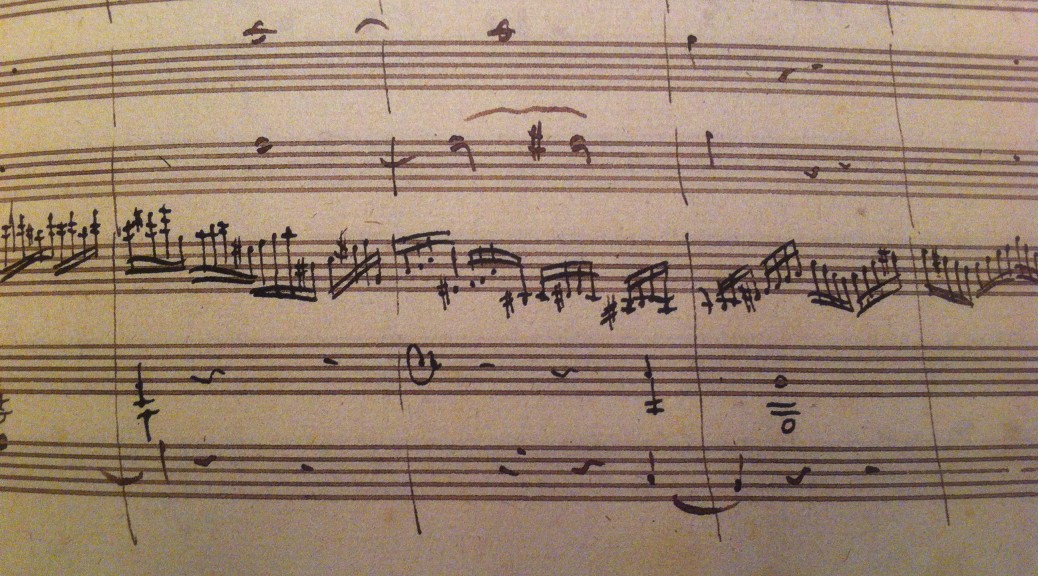

While the film “Amadeus” was largely fictional and exaggerated some of Mozart’s compositional techniques, the fact is Mozart did behold the entire structure of complex concertos, symphonies, and arias, and most of the details. There were only some details he had to “work out” on paper, as revealed in his working manuscripts. These “working manuscripts” were essentially “fair copies,” or copies one would give to a publisher to engrave, but Mozart did not make separate copies for publishers because his working manuscript, even if it had a few minor corrections, was perfectly clear enough. Even though Mozart was writing essentially “formulaic music” in that the structure and harmonic language was predetermined, the fact he wrote so many compositions within such formal and harmonic limitations, while creating such enduring and beloved undisputed masterpieces makes his accomplishment all the more astounding. He used no tricks, no gimmicks, just the pure and pristine beauty of expression in sound.

Contrast this with Beethoven, whose music is all about the “I.” It is all about Beethoven, how he thinks and feels about things, personal, political, romantic, or otherwise. Since Beethoven is about personal feeling and expression, it is likely another reason why he is the “world’s favorite” composer as I discussed in my last post. We can relate to Beethoven better than we can Mozart because Beethoven’s music is personal, emotional, and beautifully human in its imperfections, just like us, which does not mean Beethoven’s music is not great. It is phenomenal. He just had a different philosophy than Mozart and the Classicists. Beethoven embodied and championed the Romantic ideal based on personal expression. The art music world has never been the same since Beethoven, who is by far the most influential composer of all time. Now when we hear performances of music, we hear almost all music, even Bach, played through the filter of Romanticism, which was not Bach’s intention. While he definitely desired to express emotion, it was never personal. We have become “romantic junkies” as it were, desiring to hear everything through a romantic filter because we have become addicted to the warm, rich sound of Romanticism with heavy vibrato in the strings, and exaggerated dynamic and tempo changes. With Mozart, these romanticized performances of his music are even less forgivable because Mozart’s music is the complete antithesis of Romanticism. His music was never about emotion, nor was it ever about “me.” This does not mean his music cannot evoke emotion, but rather it is not about emotion. It is about the elegance, beauty, and purity of absolute music itself, regardless of whether he was expressing “darker” shades in minor keys, or “lighter” shades in major keys. Like different colors, different “shades” of music are neither “good” nor “bad,” and neither “happy” nor “sad.” These notions are romantic notions, and have nothing to do with Classicism, even though we sometimes tend to play Mozart through a romantic filter. If we bring these emotions on our own to the music, and “hear” this in the music, then so be it. It is not “wrong” to hear Mozart’s music romantically, as we all have our personal tastes and preferences, but music written from the Classical era was never personal. Beautiful and clear, yes, but never personal.

To hear Mozart’s music through a romantic filter is to compromise the pristine clarity and beauty revealed in his music since emotions, while not “good” or “bad,” inhibits clarity. This is something my best friend from college and I discussed this weekend while listening to some amazing period instrument recordings of Mozart’s symphonies by the Academy of Ancient Music under the direction of Christopher Hogwood, as well as Mozart’s piano concertos from a period instrument recording by the English Baroque Soloists under the direction of John Elliot Gardiner and played by Malcolm Bilson. In these recordings, my friend was stunned by the incredible clarity of line and balance with the period instruments, and how he could hear each individual instrument with unprecedented clarity. It was a revelation for him. It was as if he had never truly heard Mozart before. Prior to my friend’s visit to see me, he did not particularly like Mozart’s music because he had never heard it performed properly. He could now appreciate Mozart’s music and Classical era music in general far more with the discovery of period instrument performances. I recognize I had subconsciously forgiven the “romanticized” performances of Mozart’s music because of my own love of Romantic style playing. Still, my friend was correct to point out the fact Mozart’s music cannot be fully appreciated without being played as it was intended to be played.