Yesterday afternoon I had the pleasure of attending a wonderful performance at Orchestra Hall in downtown Chicago of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra playing the score of Raiders of the Lost Ark live under the direction of Richard Kaufman during the film’s presentation. For a long time I had thought it would be a great idea to hear a live orchestra accompany a film to give it a kind of “operatic” feel. When I was looking around last winter for any chance screenings of Raiders of the Lost Ark in the Chicagoland area, I was amazed to learn the Chicago Symphony Orchestra would be playing the Raiders score live with the movie this summer. Large films which contain expansive orchestral soundtracks such as Raiders of the Lost Ark, ET, Star Wars, etc., are the kind of films I have always felt would work especially well when accompanied by a live orchestra. That is why when I learned of this rare opportunity to hear the CSO accompany a screening of Raiders of the Lost Ark live, I knew this was an event I could not miss, and the presentation I heard and saw yesterday certainly did not disappoint.

I attended this performance with my two closest friends and my daughter, and we all had a great time watching this fantastic movie as well as the orchestra. I have seen Raiders more times than I can count, but have never seen a live orchestra playing this wonderful orchestral score, which was in and of itself quite fascinating. When I first saw this movie with my dad, a friend of his, and my brother when it was released in the summer of 1981, I was eight years old at the time, and thought it was the greatest movie I had ever seen. It was so much fun, the stunts so spectacular, and the music so incredibly perfect for this movie, my father decided we should stay in the theater and see the movie again. After the second viewing I knew I would be coming back to the theater to see it again and again, which I did throughout that summer and into the next year.

For Christmas, 1981, I received two very special gifts. The first was a light brown fedora my father gave me with the words “Lost Ark” embossed on the interior sweatband and my initials also stamped on the interior sweatband. I was so little my dad had to have padding added inside the sweatband so the hat company’s smallest available size could fit my head. The second gift I received was the original release of the Raiders of the Lost Ark soundtrack given to me as a Christmas gift from my mother’s side of the family. I listened to this soundtrack over and over, which helped nurture my lifelong love of music, especially orchestral music. I also eventually received a Well of Souls play set complete with twelve toy snakes I would diligently count each time I put it away to be sure I didn’t lose any, some Indiana Jones action figures and an Indiana Jones doll. I even wrote to Harrison Ford as a kid to tell him how much I admired his work on Raiders, but didn’t hear back from him. I even at one point as a ten-year old boy created my own audio version of the movie on an audio cassette recording complete with the original soundtrack recording I played on my record player in the background to accompany the “action” I attempted to realize vocally with dialogue of the characters, sound effects, etc. For those musical tracks that did not exist on the original soundtrack recording, I tried to sing the musical underscore.

As I sat in Orchestra Hall yesterday afternoon, it was like being eight years old all over again because in a very real sense I was seeing Raiders again for the first time – with live orchestra as I never had before. When I saw the Paramount logo come up and dissolve into the establishing shot of the South American mountain with the mysterious, perfectly composed music for this scene, I got chills and knew this would be every bit as good as I thought it would be. John Williams’ ingenious score came to life during this performance in a way it never had for me before, as is usually the case when hearing a live performance instead of a recording. I heard instruments I never knew played during the score because sometimes the sound effects of the final mix in a movie tend to overwhelm the music, especially in the famous scene when Indy attempts to outrun an enormous boulder. While I have listened to the soundtrack several times without the film, the balance of instruments in live performance still revealed new dimensions to the music I had never heard before. During this performance, I felt the music tended to overwhelm the sound effects on occasion, but never to the point of upsetting the overall balance of the movie as a whole. In fact, what most impressed me was Richard Kaufman’s ability to keep the musical queues spot on, such as when Marion blows smoke in the face of Toht brilliantly accompanied by a glockenspiel arpeggio. As the film came to more and more critical musical queues, such as the very many which exist in the ingenious music that accompanies the phenomenal opening scene in the jungle and the idol temple, as well as the basket chase scene, I wondered how the orchestra was going to pull them off, and they were virtually perfect on each and every queue. We sat in the very highest section of the hall center stage with a large railing in front of us like at an amusement park ride to keep us from falling forward. It was a bit disturbing to be seated on such a steep plane, but one of the benefits of being seated so high was to see how the conductor Richard Kaufman was able to keep the musical queues together with the action on screen. I noticed there were different colored vertical bars which went from left to right across a screen he had above the music stand which contained the score. Some bars were green, some were red, some were blue, and still others white. I am not sure what all the colors signified but I guessed the passing bars were an indication to the conductor of each new musical bar. Under these musical bars on this monitor was the movie itself so the conductor could see the action on screen.

Musically speaking, I was most impressed with the truck chase music and how the conductor kept the ever-changing meter and tempo changes together throughout what I consider to be the greatest musical-action sequence I have ever seen. The brass section was outstanding throughout, especially in the truck chase music which calls for them immediately at the start of this piece in 10/8 time. There were occasions in the “Raiders” theme when I did not feel the trumpets were quite as strong in this live performance as the incredible London Symphony Orchestra’s trumpets on the original soundtrack recording, but the performance of this outstanding score was still fantastic overall. The opening of the ark music was again astounding as was the Map Room music sequence which I feel is the best accompanied “non-action” sequence I have ever seen in any film. While there is no fighting, nothing blowing up, and no chasing in this scene, the music brilliantly builds with ever-increasing tension and suspense as it draws us in with Indiana Jones’ excitement in discovering the location of the Ark of the Covenant. The one orchestral element I found missing was the choral voices in the Map Room music and the opening of the ark music, but the score is so strong the choir’s absence hardly mattered. On the soundtrack however, the effect of the choir is quite powerful and would no doubt have been all the more powerful with a live choir.

I think what live performances of soundtracks accompanying a film can do is help show just how legitimate the art of film scoring is – no less legitimate and no less an art form than opera music accompanying the action on stage. All one has to do to realize just how important and how necessary a musical score is to a film like Raiders of the Lost Ark or Star Wars is to watch these movies with the sound turned down. It is striking to realize that without the music, the action on screen almost falls apart. The music is indeed the “glue” which holds scenes together and ties the audience in with an emotional connection to the action on screen in a way no other medium but music can achieve. The ability to compose music which is formally coherent while at the same time emphasizes key moments to match the action of the film to each precise moment while also being able to stand on its own as concert hall music is an incredible artistic accomplishment. While film scores can and do play on cliches as John Williams does so unapologetically in the Raiders soundtrack, that in itself is an art – to draw on common elements which trigger emotions, experiences, and archetypes, while using them in a creatively unique way. “Legit” opera composers do this all the time. Williams is a master of creating memorable leitmotifs which rival Wagner to help the audience identify through music who the villains are, who the hero is, and who the heroine is, while ingeniously adapting to his own unique style different techniques and styles of composition from late and early romanticism, impressionism, contemporary music, etc., to perfectly accompany the action on screen.

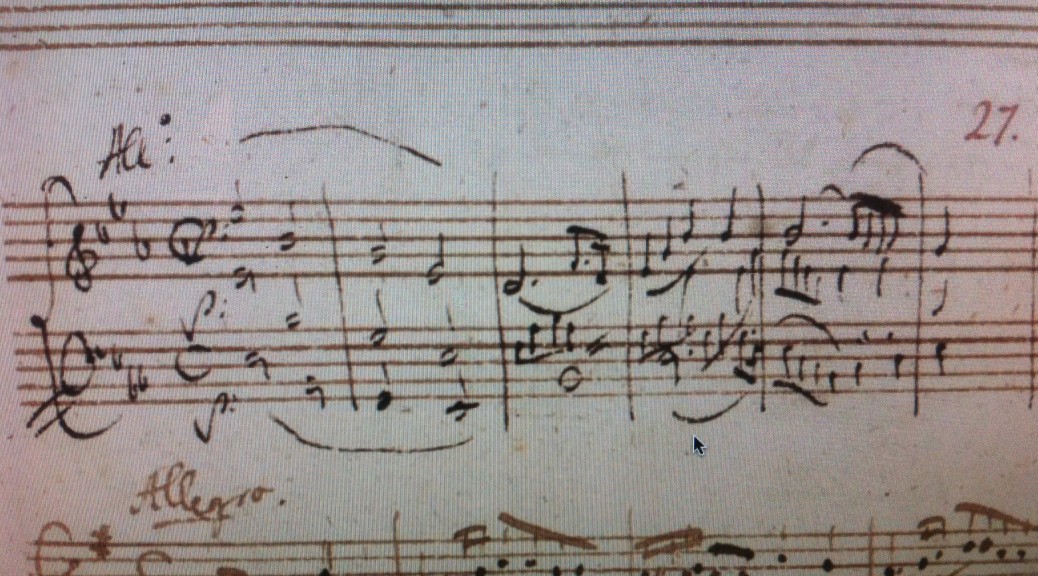

It is brilliant how Williams ironically composed the Nazi music in the late romantic style of Jewish composer Gustav Mahler, and how he also beautifully composed Marion’s music in an impressionistic style with a Debussy-like melodic and muted orchestral texture when Marion comes out in her white dress for Belloq. The music quickly dissolves to much darker tones to underscore Marion’s intentions when she covers a knife with her original clothing followed immediately by more Stravinsky-like chaotic sonorities when Indy tries to descend into the snake pit at the same time Marion also metaphorically “descends” into the snake pit of attempting to escape from the snake-like Belloq. Creativity is not the invention of truly “new” things, but rearranging old, preexisting elements in a unique way. In my college days as a music composition and piano performance major, I could sense the prejudice against film music composers as if they were Hollywood sell-outs who did not compose “legitimate art music,” but fodder for the digestion of the moviegoing masses. While this may be true for some film composers, it is important to remember that composers the art music world consider all-time masters such as Mozart wrote precisely to please his audiences so he could make money from his music. Yet one will almost never hear any criticism of the impeccable artistry of Mozart’s finest compositions, because even though they were created at least in part with a financial goal in mind, Mozart still composed some of the greatest works of musical art while still knowing how to reach his audience at the same time. The two goals are not necessarily mutually exclusive, which is a fact masters such as Mozart understood and is all too often missed by the pretentious snobbery of modern academia. The fact is, Mozart’s operas of the eighteenth century may well have been the film scores of today since his operas, like film scores today were considered eighteenth century “popular music.”

I am excited to learn the Chicago Symphony Orchestra is also scheduled to perform the orchestral score with the film ET as well as It’s a Wonderful Life. I was pleased to see such a large crowd to support this screening of Raiders of the Lost Ark accompanied by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This wonderful idea of marrying film with live orchestral accompaniment is a step in the right direction for orchestras that struggle to survive on playing “museum” pieces without also adapting to the popular culture in which they exist. Besides, film scores are no less a musical art form than any other genre of “traditional” classical music, and by the sheer numbers who come out to experience it, no less appreciated.