My first introduction to Mozart’s music was while watching the film “Amadeus” during music class in seventh grade. I was amazed by the very first notes of Mozart’s music at the start of the film with the opening chords to the overture of “Don Giovanni,” and most especially the first movement from his “Symphony No. 25 in G Minor,” K. 183 which dramatically accompanies the opening scene of Salieri’s servants discovering he has slit his throat in a botched suicide attempt. The intensity and breadth of this music, along with every other wonderful piece on this soundtrack lit a spark within me of a passion for music that has endured to this very day. After researching Mozart tirelessly upon seeing this film, I soon discovered that much of “Amadeus” was pure fiction. That did not however stop me from appreciating the music which was for me, what really made this movie. The true Mozart – the music itself was the most memorable “character” of the film – more memorable to me than any other character in this movie – the fictionalized version of Salieri and also Mozart, with the high-pitched giggle made famous by Tom Hulce, whom I nevertheless still think did an excellent job capturing amidst the fiction, much of the truthful Mozart – Mozart the brilliant performer and improviser, Mozart the sometimes arrogant and vulgar, and Mozart the driven and ingenious composer working late into the night on his scores.

One of the flaws of this otherwise remarkable “Amadeus” soundtrack is the almost total absence of any of Mozart’s chamber music. In this soundtrack, the only real chamber piece featured in the film is his wonderful “Gran Partita” for 13 wind instruments, K. 361. This is a worthy piece to be included, but the lack of his amazing string quartets, string quintets, the Clarinet Quintet, and so many other remarkable chamber works in the “Amadeus” soundtrack was I believe, a missed opportunity for the filmmakers. Since this soundtrack was my first introduction to Mozart’s music, I was therefore exposed to the kinds of works included on the soundtrack – namely his symphonies, piano concertos, operas, and more large-scale orchestral and sacred choral works, and did not really explore the wealth of riches to be found in his chamber works until many years later after my initial discovery of Mozart.

After spending countless hours listening to and researching music over the past 29 years, and particularly the music of Mozart, it is amazing to me I only recently discovered, just a couple months ago, what I believe to be his finest achievement in chamber music, if not in all of his music – namely, the “Divertimento” as Mozart entitled it, in E-flat major, K. 563 for string trio. Interestingly enough, I first learned of this Mozart work while doing research on the Beethoven string quartets, which referenced the amazing Mozart “Divertimento.” Most of mature Mozart, and also a good deal of the adolescent Mozart is of superior quality, but in this piece, Mozart reaches yet another level, even for him. When you get the very best of the best – the cream of the most perfect music, it is something so rare, it is hard to believe what you are hearing. I certainly feel that way every time I listen to the second movement of this piece especially – the glorious Adagio in A-flat major, whose perfection has moved me to tears.

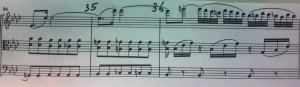

When examining the amazing last nine bars of the exposition of this second movement, we can see how Mozart sets up these last nine bars with two bars preceding it with octave leaps in the violin under a chromatic harmonic rhythm changing every beat, suspensefully leading up to the violin dissolving into an unexpected and gorgeous 32nd-note run in bar 36. It makes everything after that moment – in all of its simplicity and purity all the more striking and breathtaking.

After this stunningly beautiful 32nd-note run in the violin, he finishes the phrase on a trill in the violin which resolves in a deceptive cadence to a C minor chord in bar 38. This alone is remarkable, as a lesser composer could have simply ended the exposition here in the dominant – E-flat major.

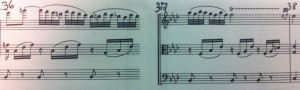

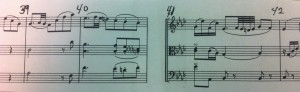

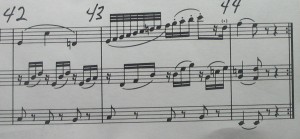

But then, Mozart continues on to yet another lovely phrase beginning with the end of bar 38, which finally resolves – again to a C minor chord in bar 42.

He does this only to continue on yet again to a third phrase, with an almost painful, poignant beauty, so moving as to outshine all of the beauty that had come before, if that were possible. finishing off this amazing exposition with another 32nd-note run to finally resolve in a lovely “sighing” cadence in the expected dominant – E-flat major.

If that were not enough, Mozart, at the end of this movement, expands the formal structure again, at the end of the recapitulation with a 15-bar long coda, beginning after the resolution to C minor again, with a continuation of the phrase in bar 111. In this coda, Mozart masterfully passes the expansive melody heard throughout the piece to each instrument, which beautifully exploits the lower to higher registers first in the viola at measure 114 (in yellow), then the cello at measure 116 (blue), and finally the violin at measure 118 (purple), finishing this exquisite movement with delicate grace notes before eighth notes, ending in a lovely high A-flat in the violin to complete 125 bars of pure elegance.

This is vintage Mozart at his finest, and these are only two of several lovely examples of his ingenious treatment of structure and musical content in this movement alone, not to mention the entire work.

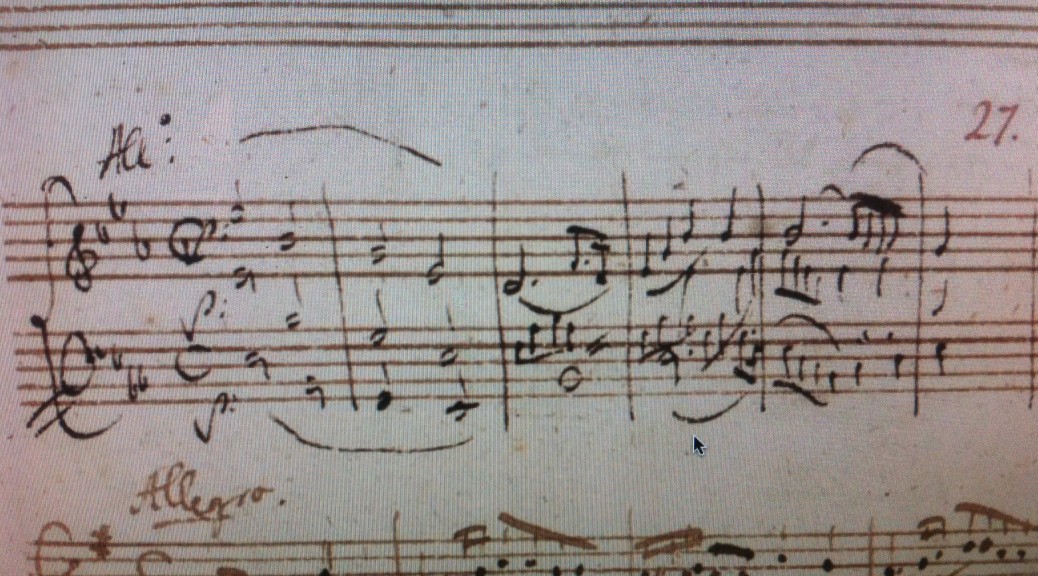

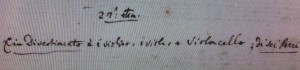

Mozart’s autograph manuscript for this “Divertimento” is missing. The piece was preserved in a set of parts in a first edition released in 1792, just months after Mozart’s death, by the music publisher Artaria and Company. The only surviving source for this composition in the composer’s handwriting can be found in his Catalogue of Works he kept from 1784 to 1791. In it, he wrote a 6-bar incipit as illustrated in the picture at the top of this post, notating the opening of the piece as was his practice when cataloging his music. On the left-hand page of his catalogue, he indicated the title and date of completion of the piece, as he did in the picture below. He entitled it, “A Divertimento” for 1 violin, 1 viola, and violoncello, in six movements.

The “Divertimento” capped a year of amazing creativity for Mozart which included some of his most enduring masterpieces, especially his last three symphonies, E-flat major, K. 543, the “Great” G minor Symphony, K. 550, and his final symphonic masterpiece, the C major “Jupiter” Symphony, K. 551, all three of which were composed over a staggering six-week period in the summer of 1788. Also composed in this amazing year was his poignant Adagio in B Minor for piano solo, K. 540, his famous C Major “Sonata Facile,” K. 545, his Piano Concerto No. 26 in D Major, the “Coronation” K. 537, and his masterly Adagio and Fugue in C Minor for strings, K. 546.

Mozart completed his “Divertimento” on September 27, 1788, just over a month after completing his last, and perhaps his greatest symphony – the “Jupiter.” The “Divertimento” is often said to have been composed for his fellow freemason friend Michael Puchberg in gratitude for his continual financial assistance to Mozart in response to several begging letters. It is possible the “trio” which Mozart says he composed for Puchberg, referred to in a letter to his wife dated April 16, 1789, could have also been one of his three piano trios composed in 1788 – the K. 542 in E major, K. 548 in C major, or the K. 564 in G major. As no dedication exists in his Catalogue of Works, it is difficult to tell which exact trio he is referring to. It is understandable given the scope and monumentality of his symphonic achievement that summer in his last three symphonies, that a composition with the unassuming title of “Divertimento” written in the fall of that same year would be overlooked in being presumably “less important” than a symphony. Still, while the very best of his symphonies, concertos, and string quartets are undisputed masterpieces, this piece has to rank at least as their equal, and in my opinion, their superior. The musical title “divertimento” was one Mozart rarely used in his maturity, but used quite frequently in his earlier youth and Salzburg years. While some of these early divertimenti are quite polished and beautifully composed, others are exactly what this music was intended to be – a “diversion” if you will – light background music to please the aristocracy and the attendees of their social gatherings. That is hardly the case with this remarkable piece Mozart composed. It is anything but a “diversion,” but rather the pinnacle of his achievements in chamber music.

The string trio may be an even more difficult compositional medium than the string quartet – a medium even a composer as skilled as Mozart found rigorous, demanding, and extremely taxing. For his “Prussian” quartets, several sketches survive, bearing witness to the effort he had to put into these “difficult works” as Mozart described them in a letter to Puchberg. Mozart also referred to his six string quartets dedicated to Haydn as “the fruits of a long and laborious effort.” This contradicts the “Amadeus” myth composition always came easliy to Mozart, with everything already finished in his head before he wrote a note down on paper. While Mozart had a superior memory and an unsurpassed awareness of musical structure, the details of his most difficult works had to be worked out through a more elaborate creative process. With one less voice than the string quartet, the string trio is even more exposed than the string quartet in such a way which leaves no margin for error for the composer. Every single note is significant, and must perfectly fit the melody, motif, phrase, partwriting, the overall structure of the movement, and indeed the entire piece. Mozart managed to accomplish this staggering feat without redundancy or mundanity. He sustains interest with exceptional mastery of form, equal and ingenious treatment of the violin, viola, and cello, passing motifs and melodies to each instrument in three-part dialogue, beauty of sound, and a striking contrast of tonalities, texture, and rhythm in the longest chamber composition he ever composed – by some readings close to an hour long.

In this one work alone, Mozart composed in most of the formal structures of his day – sonata form (first and second movements), minuet and trio (third and fifth movements), theme and variations (fourth movement), and rondo form (sixth movement). While no one work can contain everything, if I had to pick just one piece for a person to hear who had never heard Mozart’s music before, and wanted to know what his music is all about, I would pick this one. This piece virtually encapsulates every compositional skill Mozart possessed – masterful execution of counterpoint, brilliant motific development, perfect harmony, sublime melody, formal mastery, and perhaps more so than in any other composition he composed, that intangible “Mozartean” quality of being moving without sentimentality, deep without being emotional, and original without being innovative, since the wellspring from which Mozart’s music came was not of the inevitable ups and downs of his personal life, nor the desire to “outdo” his fellow composers by being innovative for innovation’s sake, but is instead the impeccable reflection of the perfect balance and oneness of the universe.